Oo Say It Again Actor Comesy

| Laurel and Hardy | |

|---|---|

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, promotional shot | |

| Nationality | British & American |

| Years agile | 1927–1955 |

| Genres | Slapstick, comedy |

| Notable works and roles | The Music Box, Babes in Toyland, Way Out Westward, Helpmates, Some other Fine Mess, Sons of the Desert, Block-Heads, Busy Bodies |

| Memorial(s) | Ulverston, Cumbria, England |

| Former members | Stan Laurel Oliver Hardy |

| Website | world wide web |

Laurel and Hardy were a one-act duo human action during the early Classical Hollywood era of American movie theater, consisting of Englishman Stan Laurel (1890–1965) and American Oliver Hardy (1892–1957). Starting their career as a duo in the silent film era, they later successfully transitioned to "talkies". From the tardily 1920s to the mid-1950s, they were internationally famous for their slapstick one-act, with Laurel playing the clumsy, childlike friend to Hardy'southward pompous groovy.[1] [2] Their signature theme song, known every bit "The Cuckoo Song", "Ku-Ku", or "The Dance of the Cuckoos" (past Hollywood composer T. Marvin Hatley) was heard over their films' opening credits, and became every bit emblematic of them as their bowler hats.

Prior to emerging equally a squad, both had well-established film careers. Laurel had acted in over l films, and worked as a writer and director, while Hardy was in more than 250 productions. Both had appeared in The Lucky Dog (1921), but were not teamed at the time. They first appeared together in a curt pic in 1926, when they signed separate contracts with the Hal Roach film studio.[iii] They officially became a team in 1927 when they appeared in the silent brusque Putting Pants on Philip. They remained with Roach until 1940, and then appeared in 8 B movie comedies for 20th Century Fox and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer from 1941 to 1945.[4] After finishing their film commitments at the terminate of 1944, they concentrated on performing stage shows, and embarked on a music hall tour of England, Ireland and Scotland.[4] They fabricated their last motion picture in 1950, a French–Italian co-product called Atoll 1000.

They appeared as a team in 107 films, starring in 32 short silent films, 40 brusque sound films, and 23 full-length feature films. They also made 12 guest or cameo appearances, including in the Galaxy of Stars promotional film of 1936.[5] On December 1, 1954, they made their sole American television appearance, when they were surprised and interviewed by Ralph Edwards on his live NBC-TV program This Is Your Life. Since the 1930s, their works have been released in numerous theatrical reissues, television set revivals, 8-mm and 16-mm home movies, feature-motion-picture show compilations, and home videos. In 2005, they were voted the 7th-greatest comedy act of all time by a UK poll of professional comedians.[six] The official Laurel and Hardy appreciation gild is The Sons of the Desert, after a fictitious congenial society in the moving-picture show of the aforementioned name.

Early careers [edit]

Stan Laurel [edit]

Stan Laurel (June 16, 1890 – Feb 23, 1965) was born Arthur Stanley Jefferson in Ulverston, Lancashire, England, into a theatrical family.[7] His father, Arthur Joseph Jefferson, was a theatrical entrepreneur and theatre owner in northern England and Scotland who, with his wife, was a major force in the industry.[viii] In 1905, the Jefferson family moved to Glasgow to exist closer to their business mainstay of the Metropole Theatre, and Laurel made his stage debut in a Glasgow hall called the Britannia Panopticon one month short of his 16th birthday.[nine] [x] Arthur Jefferson secured Laurel his first interim job with the juvenile theatrical company of Levy and Cardwell, which specialized in Christmas pantomimes.[11] In 1909, Laurel was employed past Britain'due south leading comedy impresario Fred Karno as a supporting role player, and every bit an understudy for Charlie Chaplin.[12] [thirteen] Laurel said of Karno, "In that location was no one like him. He had no equal. His name was box-function."[14]

In 1912, Laurel left England with the Fred Karno Troupe to tour the United states of america. Laurel had expected the tour to be merely a pleasant interval before returning to London; however, he decided to remain in the U.S.[15] In 1917, Laurel was teamed with Mae Dahlberg as a double deed for stage and film; they were living as common-law husband and married woman.[sixteen] The same year, Laurel made his motion-picture show debut with Dahlberg in Nuts in May.[17] While working with Mae, he began using the name "Stan Laurel" and inverse his name legally in 1931.[18] Dahlberg demanded roles in his films, and her tempestuous nature made her difficult to work with. Dressing room arguments were mutual between the 2; it was reported that producer Joe Rock paid her to leave Laurel and to return to her native Australia.[19] In 1925, Laurel joined the Hal Roach film studio as a director and author. From May 1925 until September 1926, he received credit in at least 22 films.[twenty] Laurel appeared in over 50 films for various producers earlier teaming up with Hardy.[21] Prior to that, he experienced only minor success. It was difficult for producers, writers, and directors to write for his graphic symbol, with American audiences knowing him either as a "nutty infiltrator" or equally a Charlie Chaplin imitator.[22]

Oliver Hardy [edit]

Oliver Hardy (January xviii, 1892 – August vii, 1957) was born Norvell Hardy in Harlem, Georgia.[23] By his late teens, Hardy was a popular stage singer and he operated a picture show house in Milledgeville, Georgia, the Palace Theater, financed in function by his mother.[24] For his stage name he took his father'south first name, calling himself "Oliver Norvell Hardy", while offscreen his nicknames were "Ollie" and "Babe".[25] The nickname "Babe" originated from an Italian barber near the Lubin Studios in Jacksonville, Florida, who would rub Hardy'south face up with talcum powder and say "That's nice-a infant!" Other actors in the Lubin company mimicked this, and Hardy was billed as "Infant Hardy" in his early on films.[26] [27]

Seeing picture comedies inspired him to take up comedy himself and, in 1913, he began working with Lubin Move Pictures in Jacksonville. He started past helping around the studio with lights, props, and other duties, gradually learning the craft equally a script-clerk for the visitor.[24] It was around this time that Hardy married his beginning wife, Madelyn Saloshin.[28] In 1914, Hardy was billed as "Babe Hardy" in his commencement film, Outwitting Dad.[27] Between 1914 and 1916 Hardy fabricated 177 shorts as Babe with the Vim One-act Company, which were released upward to the terminate of 1917.[29] Exhibiting a versatility in playing heroes, villains and even female person characters, Hardy was in demand for roles as a supporting actor, comic villain or 2d banana. For 10 years he memorably assisted star comic and Charlie Chaplin imitator Baton West, and appeared in the comedies of Jimmy Aubrey, Larry Semon, and Charley Chase.[30] In total, Hardy starred or co-starred in more than than 250 silent shorts, of which roughly 150 have been lost. He was rejected for enlistment past the Army during World War I due to his big size. In 1917, after the collapse of the Florida film industry, Hardy and his wife Madelyn moved to California to seek new opportunities.[31] [32]

History as Laurel and Hardy [edit]

Hal Roach [edit]

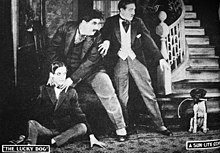

Hal Roach recounted how Laurel and Hardy became a team: Hardy was already working for Roach (and others) when Roach hired Laurel, whom he had seen in vaudeville. Laurel had very light blue eyes, and Roach discovered that, due to the technology of film at that time, Laurel's eyes wouldn't photograph properly—blue photographed as white. This problem is credible in their outset silent motion picture together, The Lucky Domestic dog, where an effort was made to recoup for the trouble by applying heavy makeup to Laurel's eyes. For about a year, Roach had Laurel work at the studio as a writer. Then panchromatic film was developed; they tested Laurel, and found the problem was solved. Laurel and Hardy were then put together in a moving-picture show, and they seemed to complement each other. One-act teams were usually composed of a straight man and a funny human, just these two were both comedians; however, each knew how to play the directly human being when the script required it. Roach said, "You could e'er cut to a close-up of either one, and their reaction was skillful for some other express mirth."[33]

Style of comedy and characterisations [edit]

The humor of Laurel and Hardy was highly visual, with slapstick used for accent.[34] They oftentimes had physical arguments (in character) which were quite complex and involved a cartoonish fashion of violence. Their ineptitude and misfortune precluded them from making whatever real progress, even in the simplest endeavors. Much of their comedy involves "milking" a joke, where a uncomplicated idea provides a ground for multiple, ongoing gags without following a divers narrative.

Stan Laurel was of boilerplate height and weight, but appeared comparatively modest and slight side by side to Oliver Hardy, who was vi ft ane in (185 cm)[35] and weighed about 280 lb (127 kg; 20 st 0 lb) in his prime. Details of their hair and wear were used to heighten this natural contrast. Laurel kept his hair short on the sides and dorsum, growing it long on meridian to create a natural "fearfulness wig". Typically, at times of shock, he simultaneously screwed upwardly his confront to appear every bit if crying while pulling upward his hair. In contrast, Hardy's thinning hair was pasted on his forehead in spit curls and he sported a toothbrush moustache. To achieve a flat-footed walk, Laurel removed the heels from his shoes. Both wore bowler hats, with Laurel'south beingness narrower than Hardy'due south, and with a flattened brim.[36] The characters' normal attire called for wing collar shirts, with Hardy wearing a necktie which he would twiddle when he was especially cocky-conscious; and Laurel, a bow tie. Hardy's sports jacket was a footling modest and washed upward with ane straining button, whereas Laurel's double-breasted jacket was loose-plumbing equipment.

A pop routine was a "tit-for-tat" fight with an adversary. It could be with their wives—often played by Mae Busch, Anita Garvin, or Daphne Pollard—or with a neighbor, often played by Charlie Hall or James Finlayson. Laurel and Hardy would accidentally harm someone'south belongings, and the injured party would retaliate by ruining something belonging to Laurel or Hardy.[34] After calmly surveying the damage, ane or the other of the "offended" parties found something else to vandalize, and the disharmonize escalated until both sides were simultaneously destroying items in front of each other.[37] An early case of the routine occurs in their archetype short Large Business concern (1929), which was added to the National Film Registry in 1992. Another short motion picture which revolves around such an atmospherics was titled Tit for Tat (1935).

Ane of their best-remembered dialogue devices was the "Tell me that again" routine. Laurel would tell Hardy a genuinely smart idea he came upwards with, and Hardy would reply, "Tell me that again." Laurel would so endeavor to repeat the thought, but, having instantly forgotten it, babble utter nonsense. Hardy, who had difficulty agreement Laurel'southward idea when expressed clearly, would then understand the jumbled version perfectly. While much of their one-act remained visual, humorous dialogue often occurred in Laurel and Hardy'southward talking films as well. Examples include:

- "Yous can lead a horse to h2o, only a pencil must be led." (Laurel, Brats)[37]

- "I was dreaming I was awake, but I woke up and found meself comatose." (Laurel, Oliver the 8th)

- "A lot of weather we've been having lately." (Hardy, Style Out West)

In some cases, their comedy bordered on the surreal, in a manner Laurel called "white magic".[34] [38] For example, in the 1937 film Fashion Out Westward, Laurel clenches his fist and pours tobacco into it every bit if information technology were a pipe. He then flicks his thumb upward as if working a lighter. His thumb ignites and he matter-of-factly lights his "pipe". Amazed at seeing this, Hardy unsuccessfully attempts to duplicate it throughout the film. Much subsequently he finally succeeds, only to be terrified when his thumb catches fire. Laurel repeats the pipe joke in the 1938 film Block-Heads, once more to Hardy'due south bemusement. This time, the joke ends when a match Laurel was using relights itself, Hardy throws it into the fireplace, and it explodes with a loud bang.

Rather than showing Hardy suffering the pain of misfortunes, such as falling down stairs or being beaten by a thug, banging and crashing sound furnishings were oftentimes used so the audience could visualize the commotion.[34] The 1927 film Sailors Beware was a significant ane for Hardy considering two of his enduring trademarks were developed. The commencement was his "tie twiddle" to demonstrate embarrassment.[34] Hardy, while acting, had received a pail of water in the confront. He said, "I had been expecting it, but I didn't expect it at that item moment. It threw me mentally and I couldn't think what to do adjacent, so I waved the tie in a kind of tiddly-widdly mode to bear witness embarrassment while trying to await friendly."[39] His second trademark was the "camera await", where he breaks the fourth wall and, in frustration, stares directly at the audience.[37] Hardy said: "I had to become exasperated, and then I simply stared right into the camera and registered my cloy."[40] Offscreen, Laurel and Hardy were quite the opposite of their movie characters: Laurel was the industrious "idea man", while Hardy was more easygoing.[41]

Catchphrases [edit]

Laurel and Hardy'southward best-known catchphrase is, "Well, hither's another prissy mess you've gotten me into!"[37] It was earlier used by W. S. Gilbert in both The Mikado (1885) and The Chiliad Duke (1896). Information technology was get-go used by Hardy in The Laurel-Hardy Murder Case in 1930. In popular culture, the catchphrase is often misquoted as "Well, here'south another fine mess you've gotten me into", which was never spoken by Hardy—a misunderstanding that stems from the championship of their film Another Fine Mess.[42] When Hardy said the phrase, Laurel'south frequent, iconic response was to commencement to cry, pull his hair up, exclaim "Well, I couldn't assistance it...", then whimper and speak gibberish.

Some variations on the phrase occurred. For instance, in Chickens Come Abode, Ollie impatiently says to Stan, "Well...", and Stan continues for him: "Here'due south another nice mess I've gotten you into." The films Thicker than Water and The Fixer-Uppers employ the phrase "Well, hither'southward some other nice kettle of fish you lot pickled me in!" In Saps at Ocean, the phrase becomes "Well, here'south some other prissy bucket of suds you've gotten me into!" The catchphrase, in its original form, was fittingly used as the last line of dialogue in the duo'southward concluding film, Atoll K (1951).

In moments of particular distress or frustration, Hardy frequently exclaimed, "Why don't you practise something to help me?", as Laurel stood helplessly by.

"D'oh!" was another catchphrase used by Hardy, and past mustachioed Scottish actor James Finlayson, who appeared in 33 Laurel and Hardy films.[37] Hardy uses the expression in the duo's first audio pic, Unaccustomed As We Are (1929) when his character's wife smashes a record over his caput.[43] The phrase, expressing surprise, impatience, or incredulity, inspired the trademark "D'oh!" of graphic symbol Homer Simpson (voiced past Dan Castellaneta) in the long-running animated comedy The Simpsons.[44]

Films [edit]

Laurel and Hardy appeared for the first fourth dimension together in The Lucky Dog (1921).

Laurel's and Hardy'southward first film pairing, although equally split up performers, was in the silent The Lucky Dog. Its production details accept not survived, just film historian Bo Bergulund has placed it betwixt September 1920 and January 1921.[45] According to interviews they gave in the 1930s, the pair's acquaintance at the time was casual, and both had forgotten their initial motion picture entirely.[46] The plot sees Laurel's character befriended by a stray dog which, afterwards some lucky escapes, saves him from being blown upwardly past dynamite. Hardy'southward character is a mugger attempting to rob Laurel.[47] They after signed split up contracts with the Hal Roach Studios, and next appeared in the 1926 film 45 Minutes From Hollywood.[48]

Hal Roach is considered the virtually of import person in the development of Laurel's and Hardy's moving picture careers. He brought them together, and they worked for Roach for over 20 years.[49] Charley Rogers, who worked closely with the three men for many years, said, "It could not have happened if Laurel, Hardy and Roach had not met at the correct place and the right fourth dimension."[50] Their outset "official" film together was Putting Pants on Philip,[51] released December three, 1927.[52] The plot involves Laurel equally Philip, a young Scotsman who arrives in the United States in full kilted splendor, and suffers mishaps involving the kilt. His uncle, played by Hardy, tries to put trousers on him.[53] Likewise in 1927, the pair starred in The Battle of the Century, a classic short involving over 3,000 cream pies; believed lost, a copy of it was found in 2015.

Laurel said to the duo's biographer John McCabe: "Of all the questions we're asked, the near frequent is, how did nosotros come together? I always explicate that we came together naturally."[54] Laurel and Hardy were joined by accident and grew by indirection.[55] In 1926, both were part of the Roach Comedy All Stars, a stock company of actors who took function in a series of films. Laurel'south and Hardy'southward parts gradually grew larger, while those of their fellow stars macerated, because Laurel and Hardy were considered slap-up actors.[56] Their teaming was suggested past Leo McCarey, their supervising manager from 1927 and 1930. During that menstruation, McCarey and Laurel jointly devised the team'south format.[57] McCarey also influenced the slowing of their comedy activity from the silent era'due south typically frantic pace to a more natural one. The formula worked and then well that Laurel and Hardy played the same characters for the next 30 years.[58]

Although Roach employed writers and directors such as H. M. Walker, Leo McCarey, James Parrott and James Westward. Horne on the Laurel and Hardy films, Laurel, who had a considerable groundwork in comedy writing, often rewrote entire sequences and scripts. He besides encouraged the cast and coiffure to improvise, then meticulously reviewed the footage during editing.[59] By 1929, he was the pair's head writer, and it was reported that the writing sessions were gleefully chaotic. Stan had 3 or four writers who competed with him in a perpetual game of 'Can You Top This?'[threescore] Hardy was quite happy to exit the writing to his partner. He said, "Later all, but doing the gags was hard enough piece of work, especially if yous accept taken as many falls and been dumped in as many mudholes equally I have. I remember I earned my money".[32] [61] Laurel eventually became so involved in their films' productions, many film historians and afficionadi consider him an uncredited manager. He ran the Laurel and Hardy prepare, no matter who was in the director'southward chair, only never felt compelled to assert his authority. Roach remarked: "Laurel bossed the production. With any director, if Laurel said 'I don't like this thought,' the director didn't say 'Well, y'all're going to do information technology anyway.' That was understood."[62] Equally Laurel made so many suggestions, in that location was not much left for the credited managing director to practise.[63]

In 1929 the silent era of film was coming to an stop. Many silent-film actors failed to make the transition to "talkies"—some, because they felt audio was irrelevant to their craft of carrying stories with body language; and others, because their spoken voices were considered inadequate for the new medium.[64] However, the addition of spoken dialogue only enhanced Laurel's and Hardy'due south performances; both had extensive theatrical experience, and could employ their voices to great comic event. Their films also continued to feature much visual sense of humor.[65] In these ways, they fabricated a seamless transition to their outset sound flick, Unaccustomed Every bit We Are (1929)[43] (whose championship took its name from the familiar phrase, "Unaccustomed as we are to public speaking").[66] In the opening dialogue, Laurel and Hardy began by spoofing the irksome and self-conscious speech of the early on talking actors which became a routine they would use regularly.[67]

Laurel and Hardy'south first feature film was Pardon U.s.a. (1931).[68] The following year, The Music Box, whose plot revolved around the pair delivering a pianoforte up a long flying of steps,[69] won an Academy Award for Best Alive Action Brusk Subject.[70] While The Music Box remains i of the duo's virtually widely known films, their 1929 silent Big Business organization is by far the most critically acclaimed.[71] Its plot sees Laurel and Hardy as Christmas tree salesmen who are drawn into a classic tit-for-tat battle, with a graphic symbol played by James Finlayson, that eventually destroys his firm and their car.[72] Big Business was added to the United States National Film Registry as a national treasure in 1992.[73] Sons of the Desert (1933) is often cited as Laurel and Hardy's best feature-length motion-picture show.[74]

A number of Laurel and Hardy films were reshot with them speaking in Spanish, Italian, French or High german.[75] The plots remained similar to the English versions, although the supporting actors were oft inverse to those who were native language-speakers. Neither Laurel nor Hardy could speak these languages, simply they memorized and delivered their lines phonetically, and received vocalization coaching. Pardon Us (1931) was reshot in all four foreign languages. Blotto, Grunter Wild and Exist Big! were remade in French and Spanish versions. Nighttime Owls was remade in both Spanish and Italian, and Below Zero and Chickens Come Home in Spanish.

Babes in Toyland (1934) remains a perennial on American television set during the Christmas flavor.[76] When interviewed, Hal Roach spoke scathingly about the picture and Laurel's behavior. Laurel was unhappy with the plot, and after an argument was allowed to make the film his fashion.[77] The rift damaged Roach-Laurel relations to the indicate that Roach said that after Toyland, he no longer wished to produce Laurel and Hardy films. Nevertheless, their association continued for another half-dozen years.[59]

Hoping for greater artistic freedom, Laurel and Hardy split with Roach, and signed with 20th Century-Fox in 1941 and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1942.[78] However, their working conditions were at present completely dissimilar: they were simply hired actors, relegated to both studios' B-film units, and not initially allowed to contribute to the scripts or improvise, as they had e'er washed.[79] When their films proved popular, the studios allowed them more input,[80] and they starred in 8 features until the end of 1944. These films, while far from their all-time work, were still very successful. Budgeted between $300,000 and $450,000 each, they earned millions at the box office for Pull a fast one on and MGM. The Fob films were so profitable, the studio kept making Laurel and Hardy comedies afterwards it discontinued its other "B" series films.[81]

The busy team decided to have a rest during 1946, but 1947 saw their first European bout in fifteen years. A film based in the charters of "Robin Hood" was planned during the tour, but not realized. In 1947, Laurel and Hardy famously attended the reopening of the Dungeness loop of the Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway, where they performed improvised routines with a steam locomotive for the benefit of local crowds and dignitaries.

In 1948, on the team'south render to America, Laurel was sidelined past illness and temporarily unable to work. He encouraged Hardy to accept movie parts on his own. Hardy's friend John Wayne hired him to co-star in The Fighting Kentuckian for Republic Pictures, and Bing Crosby got him a small part in Frank Capra'due south Riding High.

In 1950–51, Laurel and Hardy made their final characteristic-length film together, Atoll Thou. A French-Italian co-production directed past Leo Joannon, it was plagued by issues with language barriers, production issues, and both actors' serious health issues. When Laurel received the script's last draft, he felt its heavy political content overshadowing the comedy. He quickly rewrote it, with screen comic Monty Collins contributing visual gags, and hired former American friend Alf Goulding to straight the Laurel and Hardy scenes. [77] During filming, Hardy began to lose weight precipitously and developed an irregular heartbeat, and Laurel experienced painful prostate complications.[82] Critics were disappointed with the storyline, English dubbing, and Laurel's sickly physical appearance.[35] The film was non commercial successful on its outset release, and brought an finish to Laurel and Hardy's picture show careers.[82] Atoll 1000 did finally turn a profit when it was rereleased in other countries. In 1954, an American distributor removed 18 minutes of footage and released information technology as Utopia; widely released on film and video, it is the film's best-known version.

Subsequently Atoll Thousand wrapped in April 1951, Laurel and Hardy returned to America and used the remainder of the yr to balance. Stan appeared, in character, in a silent TV newsreel, Swim Meet, playing a co-director of a local California contest.

About Laurel and Hardy films take survived and are withal in circulation. Three of their 107 films are considered lost and have non been seen in complete form since the 1930s.[83] The silent moving-picture show Hats Off from 1927 has vanished completely. The get-go half of Now I'll Tell One (1927) is lost, and the second one-half has all the same to be released on video. In the 1930 operatic Technicolor musical The Rogue Song, Laurel and Hardy appear in 10 sequences, only one of which exists with the consummate soundtrack.[84]

Radio [edit]

Laurel and Hardy made at to the lowest degree 2 pilots for radio, a half-hour NBC series, based on the skit, Driver's License, and a 1944 NBC pilot.[85]

Concluding years [edit]

Post-obit the making of Atoll K, Laurel and Hardy took some months off to bargain with health issues. On their return to the European stage in 1952, they undertook a well-received series of public appearances, performing a short Laurel-written sketch, "A Spot of Trouble". The following year, Laurel wrote a routine entitled "Birds of a Feather".[86] On September 9, 1953, their boat arrived in Cobh in the Ireland. Laurel recounted their reception:

The love and affection we institute that day at Cobh was merely unbelievable. In that location were hundreds of boats blowing whistles and mobs and mobs of people screaming on the docks. We just couldn't understand what it was all about. And and so something happened that I can never forget. All the church bells in Cobh started to ring out our theme song "Dance of the Cuckoos" and Babe (Oliver Hardy) looked at me and we cried. I'll never forget that mean solar day. Never.[87]

On May 17, 1954, Laurel and Hardy made their last live stage performance in Plymouth, UK at the Palace Theatre. On December 1, 1954, they made their merely American television appearance when they were surprised and interviewed by Ralph Edwards on his live NBC-Goggle box program This Is Your Life. Lured to the Knickerbocker Hotel nether the pretense of a business coming together with producer Bernard Delfont, the doors opened to their suite, #205, flooding the room with light and Edwards' vocalisation. The telecast was preserved on a kinescope and later released on home video. Partly due to the broadcast'south positive response, the team began renegotiating with Hal Roach, Jr. for a series of color NBC Tv specials, to be called Laurel and Hardy's Fabled Fables. However, the plans had to be shelved equally the aging comedians continued to suffer from declining health.[86] In 1955, America'south magazine Idiot box Guide ran a color spread on the team with current photos. That twelvemonth, they made their terminal public appearance together while taking part in This Is Music Hall, a BBC Television program about the Grand Order of Water Rats, a British variety arrangement. Laurel and Hardy provided a filmed insert where they reminisced about their friends in British diversity. They made their final appearance on camera in 1956 in a private home movie, shot by a family friend at the Reseda, CA habitation of Stan Laurel'southward daughter, Lois. The 3-minute motion picture has no sound.[88]

In 1956, while post-obit his doctor's orders to meliorate his health due to a middle condition, Hardy lost over 100 pounds (45 kg; vii.i st), but withal suffered several strokes causing reduced mobility and speech. Despite his long and successful career, Hardy's dwelling house was sold to help cover his medical expenses.[77] He died of a stroke on August 7, 1957, and longtime friend Bob Chatterton said Hardy weighed merely 138 pounds (63 kg; 9.nine st) at the time of his death. Hardy was laid to residual at Pierce Brothers' Valhalla Memorial Park, Northward Hollywood.[89] Following Hardy'southward expiry, scenes from Laurel and Hardy's early films were seen over again in theaters, featured in Robert Youngson's silent-film compilation The Golden Historic period of One-act.

For the remaining viii years of his life, Stan Laurel refused to perform, and declined Stanley Kramer's offering of a cameo in his landmark 1963 film Information technology'southward a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.[90] In 1960, Laurel was given a special University Award for his contributions to film comedy, but was unable to attend the ceremony due to poor wellness. Actor Danny Kaye accepted the award on his behalf.[91] Despite not appearing on screen after Hardy'due south death, Laurel did contribute gags to several comedy filmmakers. During this period, most of his advice was in the form of written correspondence, and he insisted on personally answering every fan letter.[90] Belatedly in life, he welcomed visitors from the new generation of comedians and celebrities, including Dick Cavett, Jerry Lewis, Peter Sellers, Marcel Marceau, Johnny Carson and Dick Van Dyke.[92] Jerry Lewis offered Laurel a job every bit consultant, but he chose to help simply on Lewis's 1960 characteristic The Bellboy.[ citation needed ]

Dick Van Dyke was a long-time fan, and based his comedy and dancing styles on Laurel's. When he discovered Laurel'due south abode number in the phonebook and called him, Laurel invited him over for the afternoon.[93] Van Dyke hosted a goggle box tribute to Stan Laurel the year he died.

Laurel lived until 1965 and survived to see the duo'southward work rediscovered through television and classic film revivals. He died on February 23 in Santa Monica and is cached at Woods Lawn-Hollywood Hills in Los Angeles, California.[94]

Supporting cast members [edit]

Laurel and Hardy'due south films included a supporting cast of comic actors, some of whom appeared regularly:[95]

- Harry Bernard played bit parts every bit a waiter, a bartender or a cop.

- Mae Busch often played the formidable Mrs. Hardy and other characters, especially sultry femme fatales.

- Charley Hunt, the Hal Roach pic star and blood brother of James Parrott, a writer/director of several Laurel and Hardy films, made four appearances.

- Dorothy Coburn appeared in nearly a dozen early silent shorts.

- Baldwin Cooke played bit parts as a waiter, a bartender or a cop.

- Richard Cramer appeared as a scowling, menacing villain or opponent.

- Peter Cushing, well before becoming a star in Hammer Horror films, made an appearance in A Doormat at Oxford.

- Bobby Dunn appeared every bit a cross-eyed bartender and telegram messenger, too every bit the genial shoplifter in Tit for Tat.

- Eddie Dunn fabricated several appearances, notably as the belligerent taxi driver in Me and My Pal.

- James Finlayson, a balding, mustachioed Scotsman known for displays of indignation and squinting, pop-eyed "double takes," fabricated 33 appearances and is perhaps their about celebrated foil.

- Anita Garvin appeared in a number of Laurel and Hardy films, often cast as Mrs. Laurel.

- Billy Gilbert fabricated many appearances, nearly notably equally flatulent, blustery foreign characters such as those in The Music Box (1932) and Block-Heads.

- Charlie Hall, who usually played aroused, atomic adversaries, appeared well-nigh 50 times.

- Jean Harlow had a small role in the silent short Double Whoopee (1929) and two other films in the early function of her career.

- Arthur Housman made several appearances equally a comic drunk.

- Isabelle Keith was the only actress to appear as wife to both Laurel and Hardy (in Perfect Day and Be Big!, respectively).

- Edgar Kennedy, master of the "tedious burn," ofttimes appeared as a cop, a hostile neighbor or a relative.

- Walter Long played grizzled, unshaven, physically threatening villains.

- Sam Lufkin appeared several times, commonly as a cop or streetcar conductor.

- Charles Middleton made a handful of appearances, usually as a sourpuss antagonist.

- James C. Morton appeared as a bartender or exasperated policeman.

- Vivien Oakland appeared in several early silent films, and later on talkies including Scram! and Way Out W.

- Blanche Payson was featured in several sound shorts, including Oliver'southward formidable wife in Helpmates.

- Daphne Pollard was featured as Oliver's diminutive simply daunting married woman.

- Viola Richard appeared in several early silent films, most notably as the beautiful cave daughter in Flying Elephants (1928).

- Charley Rogers, an English histrion and gag writer, appeared several times.

- Tiny Sandford was a tall, burly, physically imposing character actor who played authorisation figures, notably cops.

- Thelma Todd appeared several times before her own career as a leading lady comedienne.

- Ben Turpin, the cross-eyed Mack Sennett one-act star, made two memorable appearances.

- Ellinor Vanderveer made many appearances as a dowager, loftier society matron or posh political party guest.

Music [edit]

The duo's famous signature tune, known variously as "The Cuckoo Song", "Ku-Ku" or "The Trip the light fantastic toe of the Cuckoos", was composed past Roach musical director Marvin Hatley as the on-the-hour chime for KFVD,[96] [97] [98] the Roach studio's radio station.[99] [100] [101] Laurel heard the melody on the station and asked Hatley if they could use information technology every bit the Laurel and Hardy theme song. The original theme, recorded by 2 clarinets in 1930, was recorded again with a full orchestra in 1935. Leroy Shield composed the majority of the music used in the Laurel and Hardy short audio films.[102] A compilation of songs from their films, titled Trail of the Lonesome Pine, was released in 1975. The title track was released as a unmarried in the Uk and reached #2 in the charts.

Influence and legacy [edit]

Silhouette portrait of the duo in Redcar, England

Laurel and Hardy's influence over a very broad range of one-act and other genres has been considerable. Lou Costello of the famed duo of Abbott and Costello, stated "They were the funniest comedy duo of all fourth dimension", adding "Most critics and flick scholars throughout the years have agreed with this assessment."[103] Writers, artists and performers equally diverse every bit Samuel Beckett,[104] Jerry Lewis, Peter Sellers, Marcel Marceau[105] Steve Martin, John Cleese,[106] Harold Pinter,[107] Alec Guinness,[108] J. D. Salinger,[109] René Magritte[110] and Kurt Vonnegut[109] [111] among many others, have acknowledged an artistic debt. Starting in the 1960s, the exposure on television of (especially) their short films has ensured a connected influence on generations of comedians.

Posthumous revivals and popular culture [edit]

Since the 1930s, the works of Laurel and Hardy have been released again in numerous theatrical reissues, television receiver revivals (broadcast, peculiarly public tv set and cablevision), 16 mm and 8 mm home movies, characteristic-movie compilations and abode video. After Stan Laurel's death in 1965, in that location were two major motion-picture tributes: Laurel and Hardy's Laughing '20s was Robert Youngson's compilation of the team'due south silent-film highlights, and The Neat Race was a large-calibration salute to slapstick that manager Blake Edwards dedicated to "Mr. Laurel and Mr. Hardy". For many years the duo were impersonated past Jim MacGeorge (as Laurel) and Chuck McCann (as Hardy) in children's TV shows and television commercials for various products.[112]

Numerous colorized versions of copyright-free Laurel and Hardy features and shorts have been reproduced by a multitude of production studios. Although the results of adding color were often in dispute, many popular titles are currently only available in the colorized version. The color procedure ofttimes affects the sharpness of the prototype, with some scenes being altered or deleted, depending on the source material used.[113] Their film Helpmates was the outset film to undergo the process and was released by Colorization Inc., a subsidiary of Hal Roach Studios, in 1983. Colorization was a success for the studio and Helpmates was released on home video with the colorized version of The Music Box in 1986.

There are three Laurel and Hardy museums. Ane is in Laurel's birthplace, Ulverston, United Kingdom and another i is in Hardy's birthplace, Harlem, Georgia, United States.[114] [115] The third one is located in Solingen, Deutschland.[116] Maurice Sendak showed three identical Oliver Hardy figures as bakers preparing cakes for the morning in his award-winning 1970 children's volume In the Night Kitchen.[117] This is treated as a clear case[ by whom? ] of "interpretative illustration" wherein the comedians' inclusion harked back to the writer'due south childhood.[Annotation 1] The Beatles used cut-outs of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in the cutout celebrity crowd for the cover of their 1967 anthology Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. A 2005 poll past fellow comedians and comedy insiders of the top 50 comedians for The Comedian'southward Comedian, a Tv documentary broadcast on UK'southward Channel 4, voted the duo the 7th-greatest one-act act ever, making them the top double human activity on the listing.[half dozen]

Merchandiser Larry Harmon claimed ownership of Laurel'due south and Hardy'southward likenesses and has issued Laurel and Hardy toys and coloring books. He besides co-produced a series of Laurel and Hardy cartoons in 1966 with Hanna-Barbera Productions.[120] His animated versions of Laurel and Hardy guest-starred in a 1972 episode of Hanna-Barbera's The New Scooby-Doo Movies. In 1999, Harmon produced a direct-to-video characteristic alive-action comedy entitled The All New Adventures of Laurel & Hardy in For Love or Mummy. Actors Bronson Pinchot and Gailard Sartain were cast playing the lookalike nephews of Laurel and Hardy named Stanley Thinneus Laurel and Oliver Fatteus Hardy.[121]

The Indian comedy duo Ghory and Dixit was known as the Indian Laurel and Hardy.[122] In 2011 the German/French TV station Arte released in co-production with the German language Television receiver station ZDF the ninety-minute documentary Laurel & Hardy: Their Lives and Magic.[123] The film, titled in the original German Laurel and Hardy: Die komische Liebesgeschichte von "Dick & Doof", was written and directed past German film-maker Andreas Baum. It includes many movie clips, rare and unpublished photographs, interviews with family unit, fans, friends, showbiz pals and newly recovered footage. Laurel's girl Lois Laurel Hawes said of the picture: "The best documentary well-nigh Laurel and Hardy I have ever seen!". It has besides been released every bit a Director'south Cut with a length of 105 minutes, plus 70 minutes of bonus materials on DVD.[124]

Appreciation society [edit]

The official Laurel and Hardy appreciation society is known as The Sons of the Desert, afterwards a fraternal lodge in their movie of the same proper noun (1933).[125] It was established in New York City in 1965 by Laurel and Hardy biographer John McCabe, with Orson Bean, Al Kilgore, Chuck McCann, and John Municino as founding members, with the sanction of Stan Laurel.[126] Since the grouping'southward inception, well over 150 chapters of the organization have formed beyond North America, Europe, and Australia. An Emmy-winning flick documentary about the group, Revenge of the Sons of the Desert, has been released on DVD as part of The Laurel and Hardy Drove, Vol. 1.

Around the world [edit]

Laurel and Hardy are popular effectually the world but are known nether dissimilar names in various countries and languages.

| Country | Nickname |

|---|---|

| Poland | "Flip i Flap" (Flip and Flap) |

| Germany | "Dick und Doof" (Fatty and Dumb) |

| Brazil | "O Gordo due east o Magro" (The Fat I and the Skinny One) |

| Sweden | "Helan och Halvan" (The Whole and the One-half) |

| Kingdom of norway | "Helan og Halvan" (The Whole and the One-half) |

| Spanish-speaking countries | "El Gordo y el Flaco" (The Fat I and the Skinny I) |

| Italy | "Stanlio e Ollio" too as "Cric eastward Croc" up to the 1970s |

| Hungary | "Stan és Pan" (Stan and Pan) |

| Romania | "Stan și Bran" (Stan and Bran) |

| The Netherlands, Flemish Belgium | "Laurel en Hardy", "Stan en Ollie", "De Dikke en de Dunne" (The Fat and the Skinny) |

| Denmark | "Gøg og Gokke" (Roughly translates to Wacky and Pompous) |

| Portugal | "O Bucha east o Estica" (The Fat One and the Skinny One) |

| Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia, N Macedonia | "Stanlio i Olio" (Cyrillic: Станлио и Олио) |

| Slovenia | "Stan in Olio" |

| Greece | "Hondros kai Lignos" (Χοντρός και Λιγνός) (Fat and Skinny) |

| India (Marathi) | "जाड्या आणि रड्या" (Fatso and the Crybaby) |

| India (Panjabi) | "Moota Paatla" (Laurel and Hardy) (Fat and Skinny) |

| Finland | Ohukainen ja Paksukainen (Thin one and Thick one) |

| Iceland | "Steini og Olli" |

| State of israel | "השמן והרזה" (ha-Shamen ve ha-Raze, The Fat and the Skinny) |

| Vietnam (South) | "Mập – Ốm" (The Fat and the Skinny) |

| Korea (Southward) | "뚱뚱이와 홀쭉이" (The Fat and the Skinny) |

| Malta | "L-Oħxon u fifty-Irqiq" ("The Fatty and the Thin 1") |

| Thailand | "อ้วนผอมจอมยุ่ง" ("The Clumsy Fat and Thin") |

Biopic [edit]

A biopic titled Stan & Ollie directed by Jon S. Baird and starring Steve Coogan every bit Stan and John C. Reilly equally Oliver was released in 2018 and chronicled the duo'south 1953 tour of Slap-up Britain and Ireland. The film received positive reviews from critics, garnering a 94% "Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes. For their performances, Reilly and Coogan were nominated for a Golden World and a BAFTA award respectively.

Filmographies [edit]

- Laurel and Hardy filmography

- Oliver Hardy filmography

- Stan Laurel filmography

See also [edit]

- Pekka and Pätkä

References [edit]

Notes

- ^ Sendak described his early upbringing as sitting in movie houses fascinated by the Laurel and Hardy comedies.[118] [119]

Citations

- ^ "Laurel and Hardy." Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved: June 12, 2011.

- ^ Rawlngs, Nate. "Pinnacle ten across-the-swimming duos." Archived August 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Time Magazine July 20, 2010. Retrieved: June eighteen, 2012.

- ^ Smith 1984, p. 24.

- ^ a b McGarry 1992, p. 67.

- ^ Seguin, Chris. "Forgotten Laurel & Hardy pic emerges on French DVD." Archived October 20, 2013, at the Wayback Motorcar The Laurel & Hardy Mag. December 3, 2013.

- ^ a b "Melt voted 'comedians' comedian'." Archived August 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine BBC News, January ii, 2005. Retrieved: December 3, 2013.

- ^ Louvish 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Louvish 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Louvish 2002, p. 22.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 200.

- ^ Louvish 2002, p. 25.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 159.

- ^ Louvish 2001, p. 18.

- ^ McCabe 1987, p. 26.

- ^ McCabe 1987, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 169.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 158.

- ^ Louvish 2002, p. 113.

- ^ Louvish 2002, p. 170.

- ^ Louvish 2002, p. 182.

- ^ McCabe 1987, p. 249.

- ^ Louvish 2002, p. 117.

- ^ Louvish 2001, p. 37.

- ^ a b Bergen 1992, p. 26.

- ^ Cullen et al. 2007, p. 661.

- ^ McIver 1998, p. 36.

- ^ a b McCabe 1989, p. 19.

- ^ Everson 2000, p. 22.

- ^ McCabe 1989, p. 30.

- ^ Louvish 2001, pp. 107–108.

- ^ McCabe 1989, p. 32.

- ^ a b Nizer, Alvin. "The comedian'due south comedian." Archived January 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Liberty Mag, Summertime 1975. Retrieved: December 3, 2013.

- ^ [one] Archived October 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Redfern Nick. Research into Motion-picture show. April 22, quoting from The Silent Picture, outcome vi, Spring 1970, p. four

- ^ a b c d east Bann, Richard W.. "The Legacy of Mr. Laurel & Mr. Hardy." Archived September 16, 2013, at the Wayback Automobile laurel-and-hardy.com. Retrieved: December 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Mitchell 2010

- ^ St. Marker, Tyler. "Laurel & Hardy: The Lid Facts (Part 1)." Archived March 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine laurel-and-hardy.com, 2010. Retrieved: December 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Chilton, Martin."Laurel and Hardy: It's still comedy genius." Archived June 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine The Telegraph, December 5, 2013. Retrieved: December 8, 2013.

- ^ McCabe 1975, p. xviii.

- ^ McCabe 1987, p. 123.

- ^ McCabe 1987, p. 124.

- ^ Gehring 1990, p. 5.

- ^ Andrews 1997, p. 389.

- ^ a b Gehring 1990, p. 42.

- ^ "What's the story with... Homer'south D'oh!". Archived May fifteen, 2010, at the Wayback Machine The Herald, Glasgow, July 21, 2007, p. 15. Retrieved: July 25, 2010.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 181.

- ^ Barr 1967, p. 9.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 180.

- ^ Gehring 1990, p. 273.

- ^ McCabe 1987, p. 98.

- ^ McCabe 1987, p. 100.

- ^ Gehring 1990, p. 62.

- ^ Gehring 1990, p. 263

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 229.

- ^ McCabe 1987, p. 117.

- ^ McCabe 1987, p. 118.

- ^ McCabe 1987, p. 120.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Skretvedt 1987, p. 54.

- ^ a b Mitchell 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Skretvedt 1987, p. 50.

- ^ Skretvedt 1987, p. 52.

- ^ Skretvedt 1987, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Skretvedt 1987, p. 61.

- ^ Sagert 2010, p. 40.

- ^ McCabe 1987, p. 153.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 305.

- ^ Louvish 2002, p. 252.

- ^ Gehring 1990, p. 23.

- ^ Skretvedt 1987, p. 230.

- ^ McCabe 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 38.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry List." Archived March 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Library of Congress. Retrieved: March 22, 2020.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 268.

- ^ Fullerton, Pat. "Laurel & Hardy Overseas." Archived September 6, 2012, at annal.today patfullerton.com. Retrieved: April 20, 2011.

- ^ Mitchell 2010, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Lawrence, Danny. The Making of Stan Laurel: Echoes of a British Boyhood. McFarland, 2011. Retrieved: December 7, 2013.

- ^ MacGillivray 2009, p. 6.

- ^ MacGillivray 2009, p. 9.

- ^ MacGillivray 2009, p. 190.

- ^ MacGillivray 2009, p. 126.

- ^ a b McGarry 1992, p. 73.

- ^ Dorman, Trevor. "A Guide to the lost films of Laurel and Hardy – Update." Archived Dec 17, 2010, at the Wayback Auto The Laurel and Hardy Magazine. Retrieved: April xx, 2011.

- ^ Haines 1993, p. 13.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (Baronial 27, 2018). "Laurel & Hardy Behind The Mike, Take Two". Leonard Maltin's Film Crazy . Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ a b McCabe 1975, p. 398.

- ^ Baker, Glenn A. "History'southward harbour." Archived January 10, 2012, at the Wayback Automobile The Sydney Morning Herald, March 13, 2011. Retrieved: Apr 16, 2012.

- ^ Rascher, Matthias. "1956 Dwelling movie: Laurel & Hardy together for the last time." Archived December 12, 2013, at the Wayback Motorcar |Openculture.com, May xiii, 2011. Retrieved: December 7, 2013.

- ^ Smith 1984, p. 191.

- ^ a b Bowen, Peter. "Stan Laurel dies." Archived Dec 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Focus Features, February 23, 2010. Retrieved: December 7, 2013.

- ^ "Letters from Stan.com 1961." Archived Dec 11, 2013, at the Wayback Car The Stan Laurel Correspondence Archive Projection, 2013. Retrieved: Dec 7, 2013.

- ^ [two] Archived Jan 22, 2019, at the Wayback Motorcar Dick Cavett article on meeting Stan Laurel. New York Times. Retrieved: January 29, 2019.

- ^ [iii] Archived Oct 17, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Dick Van Dyke finds his life reflects Stan Laurel'south. Baltimore Sun. Retrieved: October 16, 2019.

- ^ Smith 1984, p. 187.

- ^ "Laurel and Hardy Films: The People." Archived October 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine laurelandhardyfilms.com, Retrieved: April 3, 2011.

- ^ "The Music of Laurel and Hardy". Laurel and Hardy Central . Retrieved January thirteen, 2022.

Though it is i of those songs that seems to have always been around, like "Happy Birthday" or "Auld Lang Syne", it was really written in 1928 by Thomas Marvin Hatley. Born in Reed, Oklahoma on April 3, 1905, Hatley could play almost whatever musical instrument by and so time he entered his tardily teens. While attention UCLA in California, Hatley establish work at KFVD, a radio station located on the Hal Roach Studios lot. He wrote the simple and endearing "Ku-Ku" as a radio fourth dimension betoken.

- ^ Bann, Richard Due west. "Film notes: BRATS (1930) Hal Roach Studios". Patrick J. Picking.

- ^ "Laurel and Hardy". classicthemes.com . Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ Heath, Dave Lord. "A Walking Bout of the Hal Roach Studios Back Lot: Map, Cardinal, and Notes". Another Squeamish Mess . Retrieved January thirteen, 2022.

- ^ "Call Change History: KFVD-KPOP-KGBS-KTNQ, Los Angeles". Radio Heritage Foundation . Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ Louvish 2001, p. 267.

- ^ Louvish 2002, p. 268.

- ^ "Laurel and Hardy".

- ^ "Samuel Beckett's funny turns". The-tls.co.uk. Archived from the original on Nov 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "Some other Nice Mess: The Laurel and Hardy Story (Audiobook) by Raymond Valinoti". Bearmanormedia.com. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved Jan 17, 2019.

- ^ Rampton, James (September 1, 1998). "Arts: What a fine mess they got the states in". The Contained. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ Patterson, Michael in Brewer, Mary F. (2009) Harold Pinter's The Dumb Waiter, Rodolpi, p. 249

- ^ "Laurel Letters Sold At Auction". Laurel-and-hardy.com. Archived from the original on Nov 26, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ a b Harness, Kyp (2006) The Art of Laurel and Hardy: Graceful Calamity in the Films, McFarland, p. 5

- ^ "Laurel and Hardy: Two angels of our fourth dimension". The Independent. January 4, 2019. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ "Slapstick or Lonesome No More". Penguin.co.uk. Archived from the original on Nov 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ McCann, Chuck. "Laurel & Hardy Tribute." Archived Jan 23, 2009, at the Wayback Motorcar chuckmccann.internet: Chuck McCann, November 30, 2007. Retrieved: March 1, 2010.

- ^ Tooze, Gary. "Laurel & Hardy – The Collection (21-disc Box Prepare)." Archived April ix, 2007, at the Wayback Machine dvdbeaver.com. Retrieved: April 20, 2011.

- ^ "Laurel & Hardy Museum: Ulverston Archived Oct 20, 2007, at the Wayback Auto akedistrictletsgo.co.uk, June 2004. Retrieved: March 1, 2010.

- ^ "Laurel and Hardy Museum of Harlem, Georgia" Archived June xvi, 2019, at the Wayback Machine world wide web.laurelandhardymuseum.com Retrieved: December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Laurel & Hardy Museum Solingen" Archived December 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine www.laurel-hardy-museum.com(German) Retrieved: December 30, 2014.

- ^ Lewis, Peter. "In the Night Kitchen." Archived February 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine commonsensemedia.org. Retrieved: April 20, 2011.

- ^ Lanes 1980, p. 47.

- ^ Salamon, Julie. "Sendak in All His Wild Glory." The New York Times, April fifteen, 2005. Retrieved: May 28, 2008.

- ^ Krurer, Ron. "Laurel and Hardy cartoons by Hanna-Barbera." Archived May 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine toontracker.com. Retrieved: March one, 2010.

- ^ "The All New Adventures of Laurel & Hardy in 'For Love or Mummy'." Archived July 26, 2018, at the Wayback Car IMDb, 1999. Retrieved: March 1, 2010. Pinchot would also play the role opposite Mark Linn Baker as Oliver Hardy in the Perfect Strangers season 7 episode The Gazebo.

- ^ Pednekar, Aparna. "Bollywood comedy comes of historic period." Archived September 23, 2013, at the Wayback Auto Hindustan Times, July 8, 2014.

- ^ "Laurel & Hardy: Their Lives and Magic". IMDb. Archived from the original on June two, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ "Shop". www.laurelandhardyshop.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved Dec 5, 2018.

- ^ MacGillivray, Scott. "Welcome to Sons Of The Desert." Archived Dec v, 2013, at the Wayback Car The International Laurel & Hardy Gild. Retrieved: December 7, 2013.

- ^ Rense, Rip. "A fan gild simply for 'The Boys' : Films: The Sons of the Desert has been meeting since 1965 to honor Laurel and Hardy." Archived December 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, November 9, 1989. Retrieved: December seven, 2013.

Bibliography

- Andrews, Robert. Famous Lines: A Columbia Dictionary of Familiar Quotations. New York: Columbia Academy Press, 1997. ISBN 0-231-10218-6

- Anobile, Richard J., ed. A Fine Mess: Verbal and Visual Gems from The Crazy World of Laurel & Hardy. New York: Crown Publishers, 1975. ISBN 0-517-52438-four

- Barr, Charles. Laurel and Hardy (Movie Paperbacks). Berkeley: Academy of California Press, 1968; Beginning edition 1967, London: Studio Vista. ISBN 0-520-00085-four

- Bergen, Ronald. The Life and Times of Laurel and Hardy. New York: Smithmark, 1992. ISBN 0-8317-5459-1

- Brooks, Leo M. The Laurel & Hardy Stock Visitor. Hilversum, Netherlands: Blotto Press, 1997. ISBN 90-901046-1-5

- Byron, Stuart and Elizabeth Weis, eds. The National Society of Film Critics on Pic Comedy. New York: Grossman/Viking, 1977. ISBN 978-0-670-49186-5

- Crowther, Bruce. Laurel and Hardy: Clown Princes of One-act. New York: Columbus Books, 1987. ISBN 978-0-86287-344-8

- Cullen, Frank, Florence Hackman and Donald McNeilly. Vaudeville, Former and New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America. London: Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-0-415-93853-2

- Durgnat, Raymond. "Fellow Chumps and Church Bells" (essay). The Crazy Mirror: Hollywood Comedy and the American Epitome. New York: Dell Publishing, 1970. ISBN 978-0-385-28184-3

- Everson, William One thousand. The Consummate Films of Laurel and Hardy. New York: Citadel, 2000; First edition 1967. ISBN 0-8065-0146-4

- Everson, William M. The Films of Hal Roach. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971. ISBN 978-0-87070-559-v

- Gehring, Wes D. Laurel & Hardy: A Bio-Bibliography. Burnham Bucks, UK: Greenwood Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0313251726

- Gehring, Wes D. Film Clowns of the Depression: Twelve Defining Comic Performances. Jefferson, N Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007. ISBN 978-0-7864-2892-2.

- Guiles, Fred Lawrence. Stan: The Life of Stan Laurel. New York: Stein & Day, 1991; First edition 1980. ISBN 978-0-8128-8528-6.

- Harness, Kyp. The Art of Laurel and Hardy: Svelte Calamity in the Films. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2006. ISBN 0-7864-2440-0.

- Kanin, Garson. Together Over again!: Stories of the Nifty Hollywood Teams. New York: Doubleday & Co., 1981. ISBN 978-0-385-17471-eight.

- Kerr, Walter. The Silent Clowns. New York: Da Capo Press, 1990, First edition 1975, Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-306-80387-1.

- Lahue, Kalton C. World of Laughter: The Moving-picture show One-act Short, 1910–1930. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966. ISBN 978-0-8061-0693-ix.

- Louvish, Simon. Stan and Ollie: The Roots of One-act: The Double Life of Laurel and Hardy. London: Faber & Faber, 2001. ISBN 0-571-21590-4.

- Louvish, Simon. Stan and Ollie: The Roots of Comedy: The Double Life of Laurel and Hardy. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2002. ISBN 0-3122-6651-0.

- Maltin, Leonard. Movie Comedy Teams. New York: New American Library, 1985; First edition 1970. ISBN 978-0-452-25694-1.

- Maltin, Leonard, Selected Brusque Subjects (First published as The Great Movie Shorts. New York: Crown Publishers, 1972.) New York: Da Capo Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0-452-25694-1.

- Maltin, Leonard. The Laurel & Hardy Volume (Curtis Films Series). Sanibel Island, Florida: Ralph Curtis Books, 1973. ISBN 0-00-020201-0.

- Maltin, Leonard. The Slap-up Movie Comedians. New York: Crown Publishers, 1978. ISBN 978-0-517-53241-half dozen.

- Marriot, A. J. Laurel & Hardy: The British Tours. Hitchen, Herts, UK: AJ Marriot, 1993. ISBN 0-9521308-0-vii

- Marriot, A. J. Laurel and Hardy: The U.S. Tours. Hitchen, Herts, UK: AJ Marriot, 2011. ISBN 978-0-9521308-2-six

- Mast, Gerald. The Comic Mind: Comedy and the Movies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979; First edition 1973. ISBN 978-0-226-50978-5.

- McCabe, John. Mr. Laurel & Mr. Hardy: An Affectionate Biography. London: Robson Books, 2004; Outset edition 1961; Reprint: New York: Doubleday & Co., 1966. ISBN ane-86105-606-0.

- McCabe, John. The Comedy World of Stan Laurel. Beverly Hills: Moonstone Press, 1990; Outset edition 1974, Doubleday & Co. ISBN 0-940410-23-0.

- McCabe, John, with Al Kilgore and Richard W. Bann. Laurel & Hardy. New York: Bonanza Books, 1983; First edition 1975, East.P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0-491-01745-nine.

- McCabe, John. Infant: The Life of Oliver Hardy. London: Robson Books, 2004; Get-go edition 1989, Citadel. ISBN 1-86105-781-4.

- McCaffrey, Donald West. "Duet of Incompetence" (essay). The Golden Age of Audio Comedy: Comic Films and Comedians of the Thirties. New York: A.S. Barnes, 1973. ISBN 978-0-498-01048-4.

- McGarry, Annie. Laurel & Hardy. London: Bison Group, 1992. ISBN 0-86124-776-0.

- MacGillivray, Scott. Laurel & Hardy: From the Forties Forwards. Second edition: New York: iUniverse, 2009 ISBN 978-1440172397; kickoff edition: Lanham, Maryland: Vestal Press, 1998.

- McIntyre, Willie. The Laurel & Hardy Digest: A Cocktail of Love and Hisses. Ayrshire, Scotland: Willie McIntyre, 1998. ISBN 978-0-9532958-0-7.

- McIver, Stuart B. Dreamers, Schemers and Scalawags. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press Inc., 1998. ISBN 978-1-56164-155-0

- Mitchell, Glenn. The Laurel & Hardy Encyclopedia. New York: Batsford, 2010; First edition 1995. ISBN 978-1-905287-71-0.

- Nollen, Scott Allen. The Boys: The Cinematic Earth of Laurel and Hardy. Jefferson, N Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1989. ISBN 978-0-7864-1115-3.

- Okuda, Ted and James L. Neibaur. Stan Without Ollie: The Stan Laurel Solo Films: 1917–1927. Jefferson, Due north Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2012. ISBN 978-0-7864-4781-vii.

- Robb, Brian J. The Pocket Essential Laurel & Hardy. Manchester, U.k.: Pocket Essentials, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84243-285-iii.

- Robinson, David. The Swell Funnies: A History of Movie One-act. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1969. ISBN 978-0-289-79643-6.

- Sanders, Jonathan. Another Fine Dress: Function Play in the Films of Laurel and Hardy. London: Cassell, 1995. ISBN 978-0-304-33196-3.

- Scagnetti, Jack. The Laurel & Hardy Scrapbook. New York: Jonathan David Publishers, 1982. ISBN 978-0-8246-0278-9.

- Sendak, Maurice. In the Night Kitchen. New York: HarperCollins, 1970. ISBN 0-06-026668-6.

- Skretvedt, Randy. Laurel and Hardy: The Magic Behind the Movies. Anaheim, California: Past Times Publishing Co., 1996; First edition 1987, Moonstone Press. ISBN 978-0-94041-077-0.

- Smith, Leon. Following the Comedy Trail: A Guide to Laurel & Hardy and Our Gang Movie Locations. Littleton, Massachusetts: G.J. Enterprises, 1984. ISBN 978-0938817055.

- Staveacre, Tony. Slapstick!: The Illustrated Story. London: Angus & Robertson Publishers, 1987. ISBN 978-0-207-15030-2.

- Stone, Rob, et al. Laurel or Hardy: The Solo Films of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. Manchester, New Hampshire: Split up Reel, 1996. ISBN 0-9652384-0-7.

- Ward, Richard Lewis. A History of the Hal Roach Studios. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-8093-2637-2.

- Weales, Gerald. Canned Goods as Caviar: American Film Comedy of the 1930s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0-226-87664-ane.

External links [edit]

- Official website

- Stan Laurel at IMDb

- Oliver Hardy at IMDb

- Official The Sons of the Desert website

- The Laurel and Hardy Magazine website

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laurel_and_Hardy

Publicar un comentario for "Oo Say It Again Actor Comesy"